About

Fonio

What is Fonio?

Fonio is a gluten free ancient grain with a neutral taste that can be used by food manufacturers in a wide range of applications as a clean-label thickener, binder, or carrier.

FONIO GRAINS

Fonio’s tiny seed size allows for very fast cook/hydrations time. It can cook in five minutes, most of which is off the heat.

FONIO Flour

Fonio flour is highly hygroscopic. Its gelling and pasting capacity is up to 40% stronger than that of rice flour. It expands well into crisps when extruded.

FONIO

APPLICATIONS

Foino is used in all baked goods and other healthy food industries

FONIO

Flour

- Coatings

- Seasoning Blends

- Breads

- Crackers

- Pasta

- Drink Mixes

- Snacks

- Cereal

- Extrusions

FONIO

Grains

- Coatings

- Breads

- Crackers

- Pasta

- Beers

- Snacks

- Porridge

- Pilaf

- Salads

- Grain Bowls

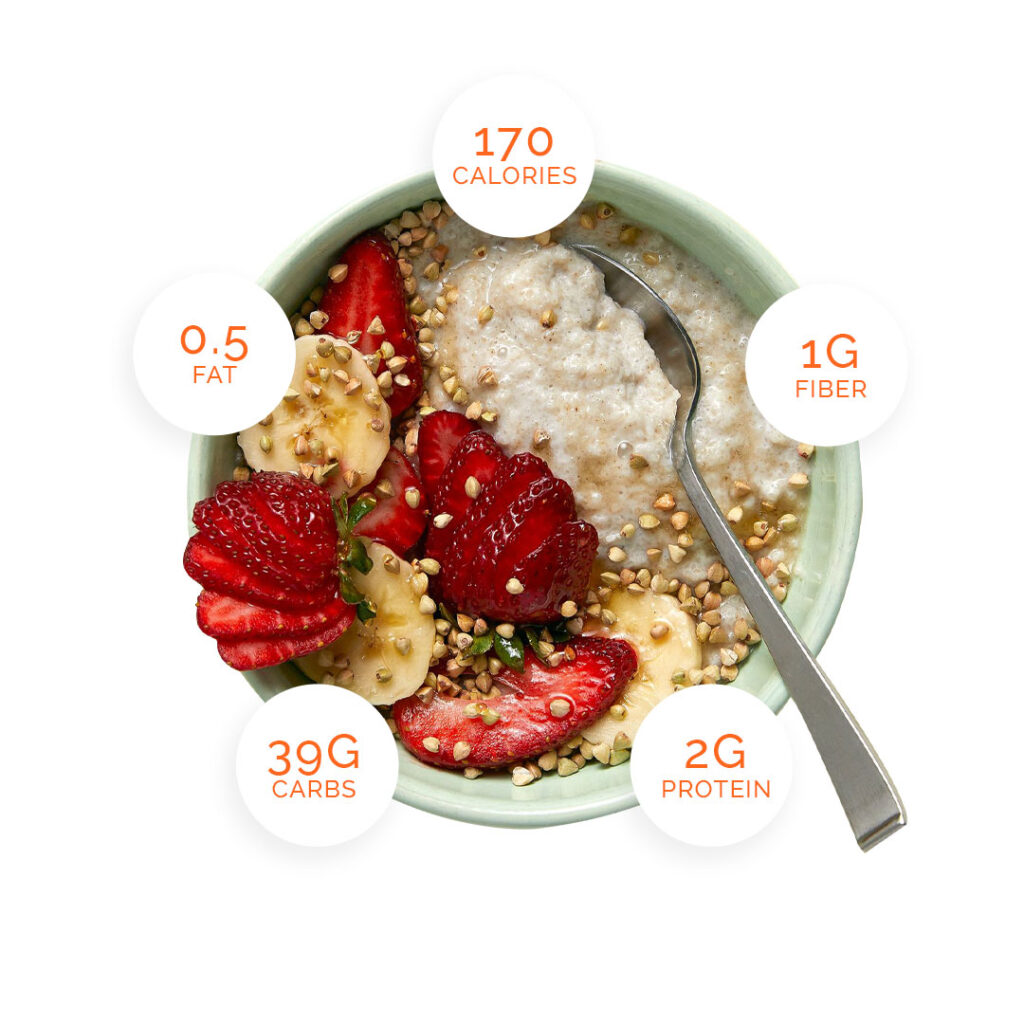

Nutrition

In West Africa, fonio is prized by pregnant women + nursing mothers, and often fed as a first solid food to babies. It’s light yet satiating, and chock-full of important micronutrients.

Strong In:

- Protein

- Iron

- Fiber

- B vitamins

- Amino acids (cysteine & methionine)

- Magnesium

- Zinc

- Potassium

- Phosphorus

- Flavonoids

- Antioxidants/Phenols]

- Fonio is a source of complex carbohydrates that are digested slowly and sustain the body with energy throughout the day.

- It is low-glycemic, making fonio a great alternative to white rice, pasta, or couscous for those watching their blood sugar levels (including people living with diabetes).

- Fonio is gluten-free, ideal for people with celiac and gluten intolerances.

- It is also a low calorie-density food. One cup of cooked fonio contains ~140 calories. (One cup cooked brown rice has 210 calories; pasta: 220 calories, quinoa: 222 calories.)

- Fonio is a good source of fiber, iron, B-vitamins, zinc, and magnesium as well as antioxidant flavonoids. And fonio is particularly high in two amino acids— methionine and cysteine— which promote hair, skin, and nail growth, and are deficient in all other grains.

- Fonio has a similar amino acid composition to that of an egg: considered to be the perfect protein.

-

Cholesterol- free

-

Low sodium

-

Gluten free

-

High fiber

History & Culture

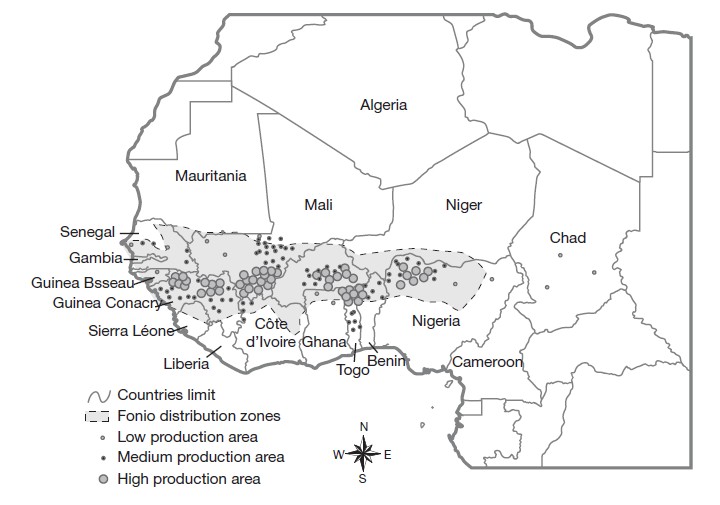

Fonio (Digitaria exilis) has been grown across the West African Sahel for over 5,000 years. From Senegal all the way to Chad, nearly every country has a fonio growing region, generally coinciding with the area whose annual rainfall is between 400 mm and 1200 mm.

Fonio is an annual plant. Traditionally, farmer sow fonio by broadcasting seed by hand onto lightly prepared ground at the first rains. Fonio has always been a rainfed crop – never irrigated. 70-110 days later (depending on the variety) fonio is harvested by hand with a sickle. In some cultures, fonio harvesters swing a basket down over the seed heads, flicking their wrist at the bottom of the swoop so that the edge of the basket dislodges and captures the seeds. Threshing is largely manual, either by beating with sticks or by trampling. Farmers use the wind to winnow away chaff, holding a basket high and pouring slowly into another basket on the ground to let the breeze carry away lighter particles. If there is not enough wind, they will fan away the chaff using large leaves or woven mattes/fans.

- Fonio thrives even in poor sandy soils, and it reaches edible maturity even during drought conditions. The fonio harvest’s reliability explains why generation after generation of West African women have planted fonio to feed their families – despite how difficult it is to turn the crop into food.

- Fonio’s seed size is perhaps the tiniest of all cereal grains – just about 1 mm in diameter. Such a small seed size poses harvest challenges for any crop, but the real problem is that each seed comes off the plant covered by an inedible husk. That husk must be removed to turn fonio into food.

Probably because fonio saves lives by preventing starvation for people living in precarious circumstances, the grain has a special place in the cultures that grow it.

- The Dogon people in Mali refer to fonio as Po – the seed of the universe, the source of all life, like the precursor to the Big Bang!

- Mothers often send their children off to their first day of school with a little sachet of fonio grains as a good luck charm.

- Fonio is served to guests of honor. Its nickname, ñamu buur, means “food for royalty.”

- It has even been found entombed in Ancient Egyptian pyramids, so valued that people believed it should be brought with them to the afterlife.

Processing

Once fonio is harvested and the seeds removed from the plants, turning the crop into food takes a lot more work.

- The essential step of dehulling is traditionally done in a large mortar and pestle, as a women’s group activity, accompanied by music to keep the rhythm flowing and the mood high. A good mood is needed for this, because it can take up to two hours to dehull just one kilogram of fonio paddy this way!

- In the last couple of decades, small machines have been introduced across the region to make that work more efficient. The newer machines do speed things up – a machine can dehull around a ton of fonio in a day – but they are no more effective at separating the husk from the kernel than the manual method. Both approaches result in a large amount of loss as operators try to remove first the husk and then the bran and germ, inevitably smashing many grains in the process, and never effectively dividing the grains into their compositional parts of husk, bran, germ, and endosperm.

- Traditional home cooks are accustomed to washing their fonio repeatedly to remove foreign matter that the traditional process leaves in the product. They steam the cleaned fonio, dry it out, and then steam it again to achieve light and fluffy results.

- Today in West Africa, there are many artisanal secondary fonio processors who perform all the steps after initial dehulling and whitening but before the final steaming, so that home cooks have a more convenient product. These processors receive dehulled and whitened but still impure fonio. They deploy a battery of women to wash away the impurities in bowls or calabashes, steam the clean fonio, dry it out, and then package it. This process is labor intensive, and it uses a lot of water. It also results in further post-harvest loss as fonio is inevitably washed away with the sand that is being removed during the many changes of water needed.

- The pre-cooking step theoretically eliminates pathogens that may reside in the fonio, but because these artisanal facilities are not set up with GFSI standards in mind, there is inevitably opportunity for cross-contamination after steaming but before packaging.

Moreover, the manual nature of processing in these facilities limits capacity. Even the largest of these secondary processors can produce at most one ton per day of fonio.

At SAF, we identified this artisanal processing situation as the obstacle to more widespread fonio usage. This is why we built SAF – to process fonio in a way that meets the quality and volume requirements of any company anywhere in the world.

Processing is where SAF shines. By applying modern grain processing technology…

- We cleanly remove the husk, leaving an intact whole grain of fonio – something that has never been seen before.

- We then remove and capture the densely nutritious bran and germ, leaving intact grains of whitened fonio, which is the local preference in West Africa – just as white rice is the preference in East Asia.

- We remove impurities to a nearly undetectable level.

- We use a kill step to eliminate pathogens.

- We comply with global food safety standards in factory layout and operations.

- We have capacity to process over 40 tons per day – and this is expandable and replicable.